The Downtown of the Future is (Almost) Here

The recent rise of Downtown Houston is a tale of two Super Bowls. What could make a more memorable bookend for an amazing period of growth and change than the most-watched sporting event in the country? The 2004 game not only introduced the world to the phrase “wardrobe malfunction,” it also arrived at the perfect time to herald the arrival of Houston’s fledgling METRORail, an impressive new convention hotel in the Hilton Americas and a glut of fly-by-night clubs along Main Street catering to Super Bowl partiers and not much else. Thirteen years later, when the Patriots again emerged victorious at NRG Stadium, visitors and locals alike could hardly fail to notice that Downtown had experienced a complete resurgence.

Barren parking lots gave way to the family-friendly splendor of Discovery Green—not to mention the vibrant redesign of Market Square Park. The combination of the Bayou Greenways project and the launch of the Houston BCycle system made it easier and more pleasant than ever before to arrive in and explore Downtown on two wheels. The METRORail has continued to expand and has been supplemented by other new and improved forms of public transit, from the Greenlink bus circulator that connects Downtown’s various destinations to a re-imagining of the city’s bus system that has drastically increased frequency (and as a result, ridership) on the most popular routes. And spending a night out in Downtown is no longer the exclusive provenance of office denizens avoiding traffic or a Super-Bowl-only gimmick.

Instead, new restaurants and bars have sprung up across the neighborhood, from the James Beard-awarded Oxheart (now Theodore Rex) in the Warehouse District to the slew of popular watering holes that have clustered around Main Street and Historic Market Square, to the buzzy new Avenida Houston campus, anchored by Hugo Ortega’s highly regarded Xochi. The debut of the Marriott Marquis and its instantly iconic Texas-shaped lazy river, was merely the largest of myriad new hotel options that have sprung up around the district, cementing its status as Houston’s premier destination for visitors.

It’s easy to imagine that these changes are the natural result of trends or demographics, as millennials lead the way back to the urban core in cities across the country. But in reality, they came about as the result of thoughtful planning by civic leaders who recognized that a strong and vibrant Downtown Houston was essential to the success of the greater Houston region. In 2004, Central Houston compiled the Houston Downtown Development Framework—part blueprint, part wish list of how to make Houston better in the two decades to come. It wasn’t the first such document—large-scale planning of Downtown began in earnest in 1994—but it was the most ambitious overview before this year.

In November 2017, the Downtown District and Central Houston in partnership with 10 other civic, government and management organizations, released Plan Downtown: Converging Culture, Lifestyle & Commerce. Planning began in earnest in the summer of 2016 and spanned 15 months of public input and expert analysis, with the goal of creating a vision of Houston in 2036, when the city celebrates its bicentennial. Just as the Allen siblings in 1836 had a vision of their outpost of the banks of Buffalo Bayou one day becoming a world-class city, Plan Downtown imagines a district transformed by new technologies, resilient in the face of extreme weather and thriving by design.

“We're in an amazing period right now. There's momentum coming in because of all the growth that has occurred. This has been accelerating for the last 30 years,” says Bob Eury, president of Central Houston and executive director of the Downtown District. “It’s a tipping point in our economy. We're at this level, but we have to start thinking about what does it take to get to the next level.”

Plan Downtown is defined by four pillars, phrased as action statements: Downtown is Houston’s greatest place to be; Downtown is the premier business and government location; Downtown is the standard for urban livability; and Downtown is the innovative leader in connectivity. Simply put, the goal is to optimize the experience of living, working, visiting and traveling Downtown.

Though they are framed individually, the four pillars are “mutually interdependent,” says Eury. As an example, he cites one of the major goals of the 2004 plan: to increase the utilization of the George R. Brown Convention Center. To increase its competitiveness for conventions and events, consultants pointed to a need for additional hotel rooms and, in particular, more options for dining and recreation in the immediate area. But to sustain restaurants and other nightlife options, leaders knew that the key was more people living Downtown. The result was the Downtown Living Initiative, which through incentives has doubled the Downtown population since 2012. To achieve these goals, the document includes over 150 individual suggestions, ranging from big-picture ideas that would affect every corner of the district and beyond to small, localized upgrades designed to subtly improve urban quality of life.

A Ring of Green

The latest unofficial symbol of Houston, created by the Houstorian James Glassman, is a simple line drawing depicting the outline and intersections of the major freeways that run through and around the center of the city—look and you’ll spot it on everything from t-shirts to the drum kit of The Suffers. But it will soon be out of date.

The biggest change heading to Downtown in the next decade is actually not one of the city’s making. In 2019, the Texas Department of Transportation (or TxDOT) plans to break ground on the North Houston Highway Improvement Project. This massive, $7 billion project will re-route Interstate 45 away from the west side of Downtown and the outdated Pierce Elevated roadway. Instead the freeway will be combined with interstates 10 and 69 to run along the north and east side of Downtown, in the process eliminating the traffic-plagued intersection where I-45, I-69 and Highway 288 intersect, currently one of the most congested exchanges in Texas.

Why? By 2036, according to the Texas Department of Transportation, nearly a million vehicles will traverse those freeways each day, yet only 13 percent of drivers are starting or ending their trip in Downtown Houston. By routing all traffic to one side of the central corridor, the project is expected to increase the flow of traffic that’s just passing through. “It’s set to increase the average speed by 24 miles per hour,” says Eury. “That's huge. TxDOT said they've never seen anything like it before.”

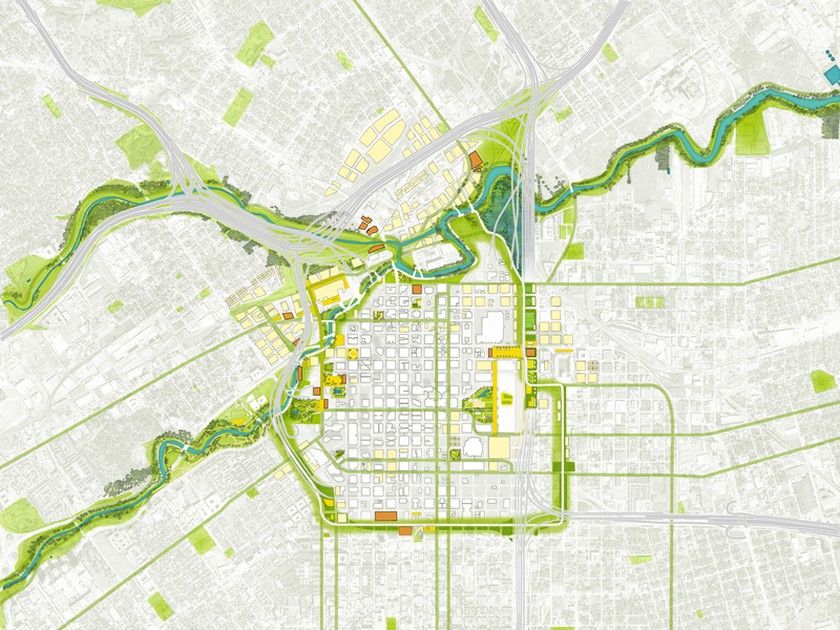

But while the benefit to commuters will be substantial when the decade-long highway project is complete, the benefit to Downtown and adjacent neighborhoods is incalculable. For the first time in 80 years, Downtown will not be hemmed in on all sides by massive edifices of concrete. “That's a once-in-a-lifetime type of opportunity,” says Eury. Instead of freeways, Plan Downtown imagines a ring of green—the Green Loop—to transform the edges of Downtown. “When those freeways were built in the 1950s, they just bulldozed right through neighborhoods. So the intention here is to reconnect them as much as you can,” he says.

Plans call for the newly expanded 69/45 freeway to be buried below grade, with a highway cap spanning several blocks installed over it at the street level, forging a strong connection between Downtown and East Downtown. The cap could be furnished with additional park space—perhaps recreational fields, to complement rather than repeat the amenities of Discovery Green—or even a semi-permanent public market. When it’s complete, aside from seeing the freeway plunge underneath in the distance, people standing on the cap might not even know that the public amenities surrounding them are technically divided between two different neighborhoods.

“On all sides of Downtown, but particularly along 59 on the east side, there’s a real physical and psychological barrier. So the North Houston Highway Improvement Project gives us these opportunities to challenge that,” says Lonnie Hoogeboom, director of planning, design and development for the Downtown District.

Along Pierce Street on Downtown’s southern border, Plan Downtown envisions a grand boulevard as one might find in a European capital, fitted with extra-wide sidewalks, space for pedestrians to congregate and a two-way bike lane as well as an allée of shade-giving trees on both sides of a multi-lane roadway.

“At the Midtown meeting, I remember in particular a couple that said when the highway project happens, the Pierce Elevated has got to come down, because that’s the one thing that prevents us from walking or riding our bikes Downtown,” says Hoogeboom. Having heard impassioned public input both for and against the idea of transforming a section of the Pierce Elevated into a distinctive attraction, á la New York’s High Line, the plan remains studiously agnostic—open to the idea, assuming someone can develop a workable plan that fits within Plan Downtown’s larger goals.

Public input was also essential to the potential redesign of the southwest corner of Downtown, where planners envision a promenade and bike path along Andrews and Heiner streets, the former of which will also highlight the Fourth Ward’s African-American history through monuments and public art.

Each section of the Green Loop offers its own attractions and benefits, but the design is more than the sum of its parts. It’s an outdoor destination that’s unique among American cities, as well as a way to rebrand Houston, presenting a new, green, 21st-century vision of the city to visitors that’s even visible from the sky. It also adds value to Houston’s other trails and outdoor amenities by offering increased connectivity and access. For cyclists, the highway cap would be perfectly situated between the Columbia Tap trail and the Lamar Cycle Track, and its proximity to major parking infrastructure (both existing and planned) make it an ideal trailhead and launching point for people to explore the Bayou Greenways.

Smart and Resilient Planning

As it happens, Plan Downtown arrives at a moment when Houston as a city is more aware than ever before of the importance of natural spaces in improving drainage and keeping development separate from particularly flood-prone areas. Hurricane Harvey hit when the plan was in its final stages, but nevertheless several of the concepts contained within it mesh well with a renewed focus on how to best protect the city’s infrastructure from flood damage.

On the northeast corner of Downtown, the North Houston Highway Improvement Project opens up a large parcel of land that can be reclaimed for enhanced storm water detention. On the West, one of the signature features of Plan Downtown is a new signature park destination, the Bayou Steps, that embodies many of the smart planning principles introduced in the design of Buffalo Bayou Park. The simple yet compelling design consists of a series of graded open spaces between the western edge of Downtown and Buffalo Bayou, offering a visual connection to the architectural gems of the Theater District. On a more practical level, the plans call for both active and resilient edges, utilizing both plants and physical structures like concrete benches to minimize the impact of flooding and create a low-lying space that would help protect and insulate some of the adjacent structures from flood events.

“Clearly as we go forward, we have to make that consideration of resiliency. The seat of our city and county government are in the flood plain, as is our performing arts district—some important geography. So there are several pieces in the plan with regard to guidelines—there’s this sense that you've got to build it better,” says Eury. “We need to be designing buildings in a way that when you have a big storm—because we know that we will have them—you just prepare for it, and you're ready for it.”

Responsive to Technology

The North Houston Highway Improvement Project and the Green Loop project represent major physical and visual changes to the fabric of central Houston, but rethinking Downtown also involves updates that will make their presence felt more than seen. The greatest challenge looking forward 20 years is imagining how technology will change how cities work, and what residents will expect of them. The popularity of ride-sharing services like Uber, the seemingly imminent arrival of autonomous vehicles and the increasing business flexibility created by smartphone connectivity in some ways offer more questions about the future than answers.

Will self-driving cars mean more or less vehicles on the streets? Should Houston have less garages—or perhaps more garage-like structures where fleets of Ubers can go in between calls? How can these new options work in tandem with public transit? These are, according to Eury, the $64,000 questions. “We know it’s changing and we are just beginning to find out how it’s all going to work. The plan is to accept that it’s coming and, quite frankly, be nimble,” he says.

That doesn’t mean city planners can’t make smart accommodations as Downtown continuously works toward attaining complete streets. As fewer people drive themselves to Downtown destinations, some street parking can be replaced with drop-off and pick-up zones that are protected from through traffic by bump-outs like the ones installed in certain sections of Midtown. Eury points out that the Greenlink buses are part of a program required by federal law to replace its vehicles every 12 years—with their expiration seven years away, that might be perfect timing for the next generation of buses to be autonomous vehicles.

“Instead of just being responsive to technology, how can we put ourselves where we are maybe doing pilot programs for certain technologies? How can we push ourselves in these areas?” says Angie Bertinot, director of marketing and communications for the Downtown District. “We can update the system of synchronized traffic lights with new technology to be more responsive to conditions on the ground, based on whether there’s a special event, or during certain times or days of the week. But what’s interesting is that it’s not just vehicles. On the streets, we could have smart lights—like when you go to the grocery store and the lights come on if a space is empty. Things like that can be implemented.”

But emerging technologies won’t just reshape the way we interact with our city—they are driving changes in the business world, too. Although the energy industry will probably always be a cornerstone of Houston’s economy, Plan Downtown imagines a slew of initiatives and partnerships aimed at reinforcing Downtown’s role as the most important regional business destination and diversifying the industries with a major presence here. On the agenda: supporting the start-up community, establishing pipelines for talent from local schools into the business arena and engaging with specialized districts like the Texas Medical Center. Among the central ideas is the establishment of an “innovation district,” composed of flexible, collaborative work spaces designed to capitalize on the city’s existing 250 early-stage software and digital technology companies, connecting small businesses and entrepreneurs to each other as well as to venture capital, angel investors and other strategic resources.

Maximizing Quality of Life

Strengthening Downtown’s appeal to the innovation economy isn’t just about office space though—it’s about maximizing quality of life. Walkability becomes of paramount importance. Smart lights, public art, shade structures and widened sidewalks can make a big difference in how safe and welcoming Downtown feels to pedestrians, but those types of improvements are just the tip of the iceberg. When it comes down to it, the district’s myriad attractions and destinations aren’t really all that far apart; they simply feel isolated because so many of Downtown’s city blocks are monopolized by big, uninteresting buildings—office towers with street-level lobbies and non-human-scale architecture, monolithic parking garages and other structures that are dead outside of office hours.

“If you're not careful when you build a parking garage, you end up with a very uninteresting streetscape, and it’s a long walk,” says Eury. “At the end of the day we still have a lot to do to improve the feel of being on the street.” One way to address this issue suggested in the plan is the creation of Downtown Development Guidelines in conjunction with the City, developers and other local stakeholders, to encourage or require ground-level redevelopment that creates an interesting streetscape in addition to offering flood protection and resilience.

Perhaps the future of Downtown development lies in following the example of residential buildings like One Park Place, with multiple restaurant concepts on its ground floor, or in commercial buildings like Hines’s new 609 Main at Texas skyscraper, which combines a soaring, architecturally impressive lobby with a dedicated corner space for a street-level shop, Prelude Coffee & Tea, and a soon-to-be-announced restaurant.

But the key to increasing walkability is the same factor that was needed to boost dining and nightlife options: more people out and about in the neighborhood at all times of day. On this front, much progress has already been made. The Downtown Living Initiative doubled the district’s population from 3,800 to 7,500, and the number of Downtown hotel rooms has skyrocketed from 1,200 in four hotels in 2000 to 8,300 across 27 hotels as of 2018. By 2036, officials hope to raise the number of people living Downtown to 30,000, occupying 12,000 apartment units.

“Looking at other central cities, there tends to be this inflection point—once you get to 20,000 or 30,000 in population you start to get a sense of bustle and activity,” says Hoogeboom.

More people isn’t the only goal—planners hope Downtown can become more family-friendly with the eventual addition of public elementary and middle schools (with the High School for the Performing and Visual Arts leading the way, opening its new Downtown campus in 2018), new child-care options and more resident-supporting retail and service businesses. Another suggestion is the development of student housing for those attending the University of Houston, Rice University, Texas Southern University and graduate programs in the Texas Medical Center, all of which are easily accessible from Downtown via the METRORail.

Plan Downtown also identifies six emerging residential neighborhoods Downtown and notes that additional development should be encouraged to target these zones, creating pockets of dense livability and individual neighborhood character. Plan Downtown does not suggest coming up with nicknames for these micro-neighborhoods, but since EaDo has been so successful since the adoption of the abbreviated moniker, it seems like a good idea. Perhaps soon we’ll be referring to not only Market Square, but also SoDo (South Downtown), Little Warehouse (Warehouse District), Caroline (adjacent to Minute Maid Park) or Four Corners (around the center of Downtown where the original wards were divided).

An Authentic Downtown Experience

The central issue—one that covers the cornerstones of making Downtown a better place to visit, live, work and travel—is how to make Downtown the kind of place where people can enjoy themselves without a specific itinerary or destination.

“One of the things we talked a lot about in meetings is, ‘If I was staying at Le Meridien or Hotel Alessandra, and I have three hours before I leave for the airport what would I do in Downtown?’ And other than park space, or going to a restaurant, or getting a drink somewhere, we're lacking a little bit,” says Bertinot. “How can you have that authentic experience? We want to be this place where you don’t have to have a plan.”

Interestingly, Eury’s biggest complaint about the 150-plus ideas in Plan Downtown is that they aren’t ambitious enough—he thinks the Houston it imagines could become reality well before 2036. “There’s too much in here that’s too soon and not enough that’s far-reaching,” he says.

Maybe he’s right—in Space City, reaching for the stars is considered standard operating procedure. But if the Super Bowl returns in another dozen years or so, the Downtown that visitors find will almost certainly be more engaging, more vibrant and better connected to the city at large.

Every 200-year-old should be so lucky.

Mentioned in this Post

Prelude Coffee & Tea

609 Main St

Minute Maid Park

501 Crawford St

Discovery Green

1500 McKinney St

George R. Brown Convention Center

1001 Avenida De Las Americas

Market Square Park

301 Milam St

Marriott Marquis Houston

1777 Walker St

Buffalo Bayou Park

One Main St

Hilton Americas-Houston

1600 Lamar St

Le Meridien

1121 Walker St

Avenida Houston

1001 Avenida De Las Americas